By Wayne E. Simsic

In his autobiographical account, Report to Greco, Nikos Kazantzakis tells of a time when his inner life had dried up so dramatically that he decided to seek counsel from a hermit who lived in a cave on Mount Athos in Greece. The hermit counseled faith and patient waiting but Nikos wanted answers.

“How long?”

“Until salvation ripens in you. Allow time for the sour grape to turn to honey.” “And how shall I know, Father, when the sour grape has turned to honey?”

“One morning you will rise and see that the world has changed. But you will have changed, my child, not the world. Salvation will have ripened in you. At that point surrender yourself to God, and you shall never betray Him.”

The seeker returned to his cell and one morning awoke to a medlar tree blossoming and giving off a sweet smell even though it was the dead of winter. Nikos wept. “I came here to the desert and buried myself inside this cell with its humble bed, its jug of water, its two stools. Now I am waiting. Waiting for what? God forgive me, but I really do not know very well. This doesn’t bother me, however. Whatever comes will be welcome.”2

Such open-ended waiting at a time of crisis is not reinforced in our culture; we tend toward impatience and a quick fix to take away pain and suffering. We may enter the desert willingly, but we want answers. Nevertheless, on the level of faith, we realize that we should trust this journey into the darkness. Like the Magi, depicted in the T.S. Eliot poem, we hear “voices singing in our ears” telling us that this journey into the night desert is folly but we also know that we have lost our taste for the old ways of security and comfort.3 Like the early Desert Christians, we intuit that the journey will be one of dying, dislocation from the usual way of seeing and understanding self and the world, but we realize that dying is necessary. Answering the desert call stretches the spirit but also opens the eyes, focuses attention on the one thing most important.

Answering the desert call stretches the spirit but also opens the eyes

Many today wander in a soul-withering desert brought on by the suffering of job loss, setback, or an abiding concern for the struggling economy, war, and ecological destruction. The pain goes deep. We can pretend to get on with our lives but inner discontent shows itself in fear and anxiety. The insecurity we feel serves as a wake-up call to a new vision, one that releases us from unnecessary worry and dread. We can choose to embrace the desert and its fertile darkness for the truth it can teach us or flee.

The question is: are we willing to stay put long enough, to wait in the darkness, and to trust that the waiting will be fruitful? Do we believe that inner balance and even spiritual renewal can be found at a time of desolation and seeming loss of hope? Are we willing to listen to the voice of truth that releases us from cultural expectations and prejudiced ways of seeing so that we can discover a new vision? In spite of his hesitation and impatience, Kazantzakis discovered that the darkness can be fertile, a dwelling place of God, where all is renewed.

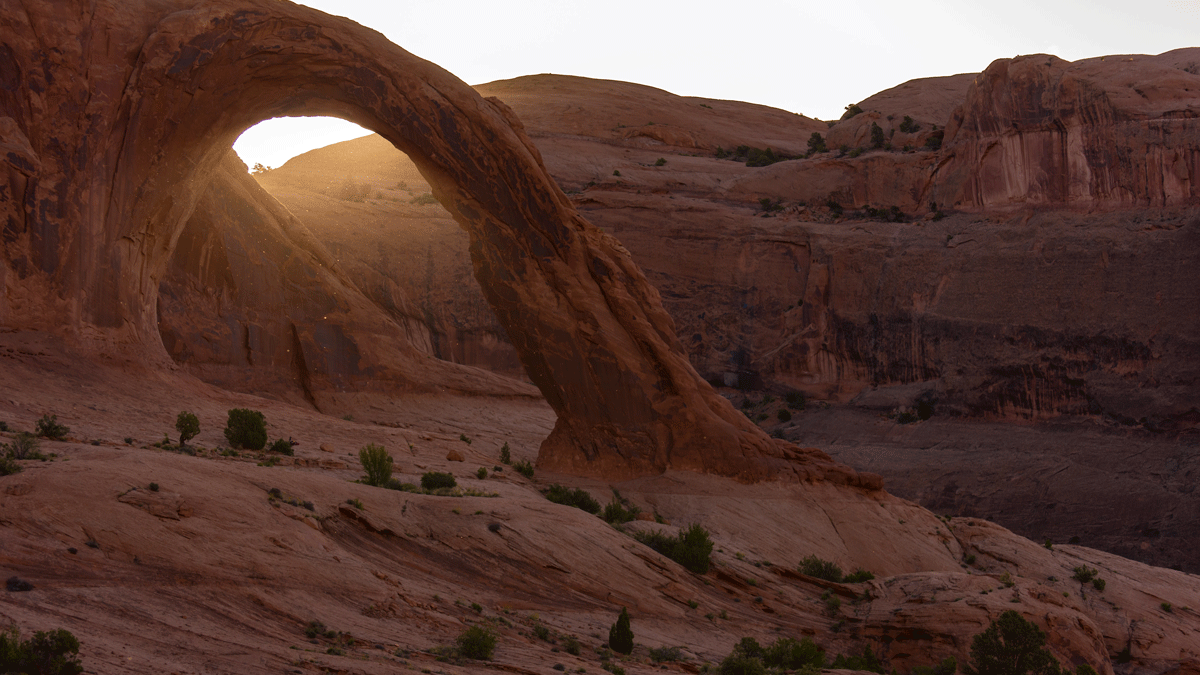

During a retreat at the Monastery of Christ in the Desert in New Mexico, I took a walk late at night. The darkness was haunting and the moonlight just strong enough to accent the rough outlines of the canyon walls that extended like massive arms embracing the monastery and the desolate landscape that surrounded it. The rock face itself seemed chiseled and alive like a Brancusi sculpture. In the background the Chama River mumbled as it made its way over rock and sand, a sound that did not disturb the stillness but heightened it.

I had been on retreat for two days and the harsh environment was no longer foreboding. On this particular night my walk was actually a kind of homecoming; the shroud of darkness, the stillness and the barrenness of the surroundings seemed an invitation to mystery that I yearned for but had difficulty accepting.

Many fear the darkness they encounter during desert times because they assume it will be negative, an experience of disintegration or even punishment. Though at first the darkness may unsettle us because it removes our comfort zone and prompts us to trust the unseen, it has the potential to become a balm for an ailing soul. It may introduce us to an inner freedom, a release from the narrow view of self that weighs down the soul. A desert landscape that at first seemed barren and stark has the potential to intensify vision and reveal hidden color and spectacular form.

When the teachings of St. John of the Cross concerning the dark path of the soul were found by a group of Carmelite nuns to be too harsh, he referred them to his poems and told them that in the metaphors they would find his original inspiration. For John, darkness is poetry: it does not bear down on the soul but rather buoys it with love, namely “the living flame of love.”4 It is this love that lures us toward an infinite horizon where God can get our attention. In the deep stillness of a dark night a hush comes over the soul and the Spirit has room to work:

O guiding night!

O night more lovely than the dawn!5

Darkness for John was more like a lover’s dance. The flame of love intensifies our longing for a deeper experience of God. We do not encounter an obscure, inaccessible God, one who elicits fear and retains a formidable distance between the human and divine, but rather a playful God who hides as a way of feigning absence inviting us into a cloud of unknowing where only the love will satisfy us. Reading the poetry of John of the Cross, especially “The Dark Night” and “The Spiritual Canticle,” we find ourselves pulled in by God’s playfulness, engaged in a divine game of hide and seek. Eventually the seeker asks with a heavy heart:

Where have you hidden,

Beloved, and left me moaning?6

Inevitably the darkness will mean sacrifice because love needs room to grow. We are summoned to transformation. The early Desert Christians offer guidance because they separated themselves from cultural turmoil to focus on what it means to journey into the unknown as a disciple of Christ. We do not have to abide in a geographical desert to benefit from their call. They were not trying to escape society—in fact the desert, due to its harshness, required of them an attitude of hospitality— but rather to ground themselves more fully in the ways of the Spirit.

Answering a desert monk’s request for spiritual guidance, Abbot Moses replied: “Go sit in your cell, and your cell will teach you everything.”7

This counsel may have disheartened the monk because, after all, he had remained true to his cell and was being asked to return to it, stay put, and continue facing the death of his own self-interest, desires, and self- righteousness. As we retreat to an inner cell, our own encounter with divine presence throughout the day, we realize that it is a “place” not of tranquility but of inner upheaval. We are called repeatedly to this inner sanctum not to flee the small deaths that we experience throughout the day but to encounter them deeply.

Eventually the dimensions of our cell grow to include more and more of our lives and we realize that we are being called to complete surrender to divine presence; nothing should be held back. Desert monks spoke of purity of heart, a single-minded focus on the divine image in every aspect of our lives, grounded in the intuitive awareness that we are called to lose ourselves completely in God. There is a Sufi tale in which a pilgrim, upon death, arrives at the gate of heaven. A voice inside asks, “Who is there?” The pilgrim answers, “It is I, Lord.” The voice responds, “Return to earth and continue your journey.” Years later the pilgrim arrives at heaven’s gate again. The voice asks, “Who is there?” The pilgrim answers, “It is you, Lord.” The reply: “Enter.”8

According to desert saints, those who remain true to the cell discover quies, a profound “rest” that is the fruit of an inner freedom not disturbed by the fluctuations of outer events. Thomas Merton described this rest as a “kind of simple no-whereness and no-mindedness that had lost all preoccupation with a false or limited ‘self.’”9 In other words, how can anxiety and fear survive when one drops anchor again and again into the calm depths of the Self? This quest for purity of heart unveils the illusion of an external self, namely our attachment to things and ideas, and opens us to self-understanding and truth. As a result, we discover the capacity to open our hearts to others and listen deeply to the “word” being spoken in our lives.

While attending Lauds with the monks on retreat I found myself distracted by the rough-shaven log I was sitting on as well as the intermittent coughing and off-key singing of the early morning worshipers, including myself. Eventually I caught a glimpse of light splashing through the high window that faced the canyon wall. The sun was beginning to rise over the craggy heights and spill light everywhere. Slowly the figures that were once in shadows emerged in a soft glow and the cold voices became warm, more awake and lyrical. All of this startled me because it seemed as if the entire place had been recreated by an extravagant outpouring of grace.

We find it difficult to appreciate the abundance of grace especially in the dark times. Waiting in his desert cell with patience, Nikos Kazantzakis witnessed the medlar plant blossoming in its own time. John of the Cross and the Desert Christians teach us that grace never abandons us and unfolds in mysterious ways in times of crisis. Each of us, throughout our lives, finds ourself led repeatedly into the desert to be emptied. Eventually we learn to open our hearts to the fertile seed that grows there and to bear the mystery of this waiting; we discover that we are able to appropriate the truth of our lives in peace and with an unexplainable freedom.

So how do we respond to those times when physical comfort and security, along with spiritual consolation seem to desert us? Let us nurture an inner cell that represents our trust in the Spirit’s hidden work. Why not remember this cell throughout the day using a word or phrase from Scripture to recall it? Withdraw to this desert place as a home that we hold open in our heart, a deep inner silence that we trust heals and leads us into the realm we long for but only see “through a glass, darkly” (1 Cor. 13:12, KJV).

Reflection Question

“Many fear the darkness they encounter during desert times because they assume it will be negative, an experience of disintegration or even punishment,” writes Simsic. “Though at first the darkness may unsettle us because it removes our comfort zone and prompts us to trust the unseen, it has the potential to become a balm for an ailing soul.” Recall a time when you or someone you know experienced darkness as a healing force.

Excerpted from “For Darkness Is As Light” by Wayne E. Simsic. Originally published in Weavings: A Journal of the Christian Spiritual Life, November/December 2010/January 2011), Vol. 26, No. 1. Copyright © 2010 by The Upper Room.

Endnotes

1 The title "For Darkness Is As Light" is taken from Ps. 139:12, RSV.

2 Nikos Kazantzakis, Report to Greco (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1965), 286.

3 T.S. Eliot, “Journey of the Magi” in Selected Poems (New York: Harcourt, Brace and World, 1964), 97.

4 The Collected Works of St. John of the Cross, trans. Kieran Kavanaugh and Otilio Rodriguez, 2nd ed. (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1964), 578.

5 The Collected Works of St. John of the Cross, 296.

6 The Collected Works of St. John of the Cross, 410.

7 Thomas Merton, The Wisdom of the Desert (New York: New Directions, 1960), 30.

8 This Sufi story surfaced often in my reading but was not footnoted. A secondary source with a version different than what I have used can be found in William Shannon, Silence on Fire (New York: Crossroad, 2000), 11.

9 Merton, The Wisdom of the Desert, 8.

Share on Socials